I like to doodle. In a notebook, on a napkin, on the back of an envelope, it doesn’t matter. I just need a single pencil. While having many pencils of different colors is fun, the first one I find is the best. That’s the one that lets me go from a blank piece of paper to a picture.

Air pollution monitoring works the same way. The most valuable monitor a country has is its first monitor. It shifts a country from having no information about its air quality to having something. Importantly, that first step also provides the largest increase in local human capacity to address air quality.

Yet 39% of countries lack even a single government air quality monitor that publicly shares data. This prevents many countries from measuring progress toward their air quality standards – if they have them. In fact, more than 100 countries and territories do not have any annual standards for fine particulate matter (PM2.5), the most harmful air pollutant to our health. Such standards are necessary for building regulatory policy – and the first monitors in a country help set those standards.

What about using satellite-derived data for providing information where no monitoring on the ground exists? While satellite-derived data can be a valuable resource for getting a snapshot of the air pollution that exists in any corner of the earth, it has limitations. It can’t provide the fine-grained hourly or daily data at the resolution and quality that are needed to measure sub-annual air quality standards or enforce regulations. Also, satellite-derived estimates rely on models that use existing ground monitoring data. If ground monitoring data in a particular region is not available, it can make these satellite-derived estimates less accurate. There is no substitute for locally-collected ground monitoring data, nor the local technical and policy capacity that collecting monitoring data builds.

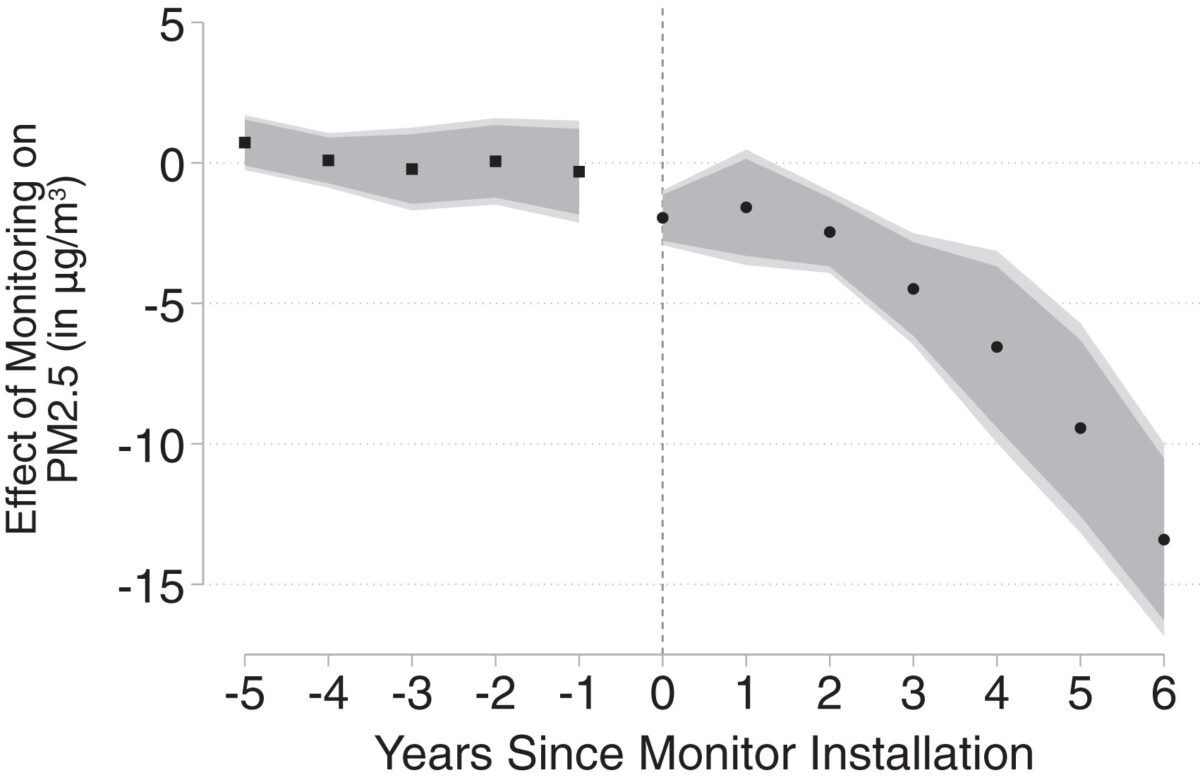

Research shows that one air quality monitor on the ground can have a big impact over time. For example, a recent study finds a single air quality monitor running in a city over a five-year period can translate into clean air gains that provide roughly a year of extra life expectancy for citizens.

The value of the first monitor a country puts up is enormous, which is why we have published the report, ‘The Case for Closing Global Air Quality Data Gaps with Local Actors: A Golden Opportunity for the Philanthropic Community.’ It analyzes precisely where the greatest opportunities exist for small-scale monitoring efforts to make a national impact in places with no or very little air quality data.

Our study factors in a country’s air pollution levels (estimated with satellite data), current monitoring, relevant development assistance, and local experts’ inputs. The report identifies 46 ‘high opportunity’ countries where a $50,000-100,000 annual investment in each could achieve a national-level impact by closing air quality data gaps.

The top 10 ‘highest opportunity’ countries we identify:

| 1. Democratic Republic of Congo | 6. Lesotho |

| 2. Cameroon | 7. Zambia |

| 3. Honduras | 8. Angola |

| 4. Equatorial Guinea | 9. Central African Republic |

| 5. Bhutan | 10. Republic of the Congo |

Other countries with populations greater than 100 million that are on the list are Egypt, Pakistan, Nigeria, and Bangladesh.

Key findings from the report:

- 838 million people in the 46 ‘highest opportunity’ countries are breathing air pollution (PM2.5) levels four times higher than the World Health Organization’s (WHO) guideline. 28 of these countries lie in Africa, 10 in Asia, seven in South America and one in Europe.

- In these 46 countries, there are a total of 34 government-run PM2.5 monitors online. This is less than the number of government-run PM2.5 monitors in Finland, a country with ~1/150th the population and pristine air.

Our analysis estimates that globally it would take $4-8 million per year to support local experts to substantially close air pollution data gaps. If just one small country from our list succeeds in reducing its pollution levels by putting up a single monitor – as research predicts it would– the avoided health care costs in that one country alone would cover the total global investment cost.

Helping countries go from zero to one on air quality monitoring is a golden opportunity for the philanthropic community to improve the air we breathe. We can’t let that opportunity slip through our fingers.