In Warsaw and the wider Masovian region, rapid urban growth paired with insufficient public transport infrastructure has fuelled an increase in vehicle traffic, leading to significant transport-related air pollution. While prior government audits have largely focused on emissions from household heating, cars remain a substantial, yet often overlooked source of pollutants, such as nitrogen oxides (NOx), particulate matter, carbon monoxide, and heavy metals.

These emissions cause significant problems: 97% of European residents breathe air that doesn’t meet World Health Organization (WHO) standards. What’s more, 21 of the 50 most polluted European cities are in Poland, and every year around 6,000 premature deaths in Masovia (one of 16 regions of Poland) can be attributed to poor air quality. The transport sector contributes about 8% of PM10 emissions of the entire country, while in Warsaw, the capital, it’s 63%.

Children are especially vulnerable to these pollutants. Their shorter stature and higher breathing rates expose them to greater concentrations of vehicle emissions. Daily exposure to nitrogen dioxide (NO2) immediately impairs cognitive functions, affecting school performance and causing a decrease in test results. Chronic exposure to traffic related air pollution can exacerbate respiratory conditions and contribute to lifelong health problems. The WHO recommends that short-term human NO2 exposure should not exceed 25 µg/m³, with an annual limit of 10 µg/m³.

The solution

The “School Streets” initiative, led by the Road Safety Partnership of Poland (Partnerstwo dla Bezpieczeństwa Drogowego), aimed to combat transport-related air pollution by combining air quality monitoring with community-focused urban planning. The project’s objectives were to measure pollution levels, raise public awareness, and propose actionable solutions to protect children from air pollution.

Specialised air quality sensors were deployed at five urban elementary schools across the Masovian region: Nowy Dwór Mazowiecki, Legionowo, Piastów, Płońsk and Warsaw-Wawer. Each site featured two sensors: one positioned by the main entrance at the street side of a school to capture pollution from traffic and the other placed behind the school, metres away from the road and shielded by the building (serving as a control measure to compare to the sensor by the road). The research spanned both warm and cold seasons to account for meteorological and seasonal variations (i.e. impacts of pollution from household heating, often based on coal and wood boilers and stoves). Additionally, traffic flow was meticulously monitored, including the number of vehicles, their types, and instances of idling near schools.

The air quality monitoring revealed alarmingly high pollution levels near schools. In Legionowo, one of the five pilot locations, NO2 concentrations peaked at an astonishing 700 µg/m³ during idling near school at drop-off and pick-up hours. This figure is nearly 30 times higher than the WHO’s recommended short-term exposure limit of 25 µg/m³. These peaks occurred near sensors installed by the main school gate, near a street, where vehicle idling and high traffic intensity coincided with children’s presence in the area. Even on weekends, NO2 levels by the street reached up to 30% higher than those recorded in less trafficked areas behind the school.

The same patterns were noted in all five project locations – the peaks were registered by the sensor located by the street, during drop-off and pick-up hours on school days. The differences between sensor locations were always significant but sometimes more visible on less windy days. The findings highlight a critical issue: urban schoolchildren in areas with heavy traffic are exposed to extreme levels of harmful pollutants, posing immediate and long-term health risks.

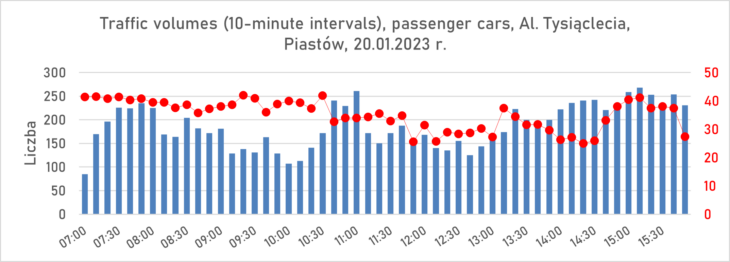

Traffic intensity measurements allowed for a very precise correlation of air pollution with the number of vehicles in front of each school. Each of the project locations had different traffic characteristics, but in front of the “record” school during peak traffic hours there were even over 2,200 vehicles per hour in winter and over 1,550 vehicles per hour in summer. Peak values at other locations ranged from 50 to 500 vehicles during rush hour.

Barbara Król, Road Safety Partnership of Poland

Key recommendations derived from the data included:

- Traffic measures: Eliminating the hazard by introducing one-way streets, elevated crossings, and traffic-calming zones (20 km/h speed limits) around schools to reduce vehicle emissions, changing mobility patterns, encouraging mobility alternatives, e.g. independent walking, cycling, public transport, etc.

- Improved school access: Increasing space for pedestrians and cyclists, creating additional back entrances to schools to divert foot traffic away from high-emission areas, removing car parking at school grounds; improving the aesthetics of a school street by organising spaces with dedicated functions: communication, walking, cycling and recreation.

- Greener school areas: Introduction of insulating greenery in front of the school premises, increasing green areas in the street space, renovating school playgrounds distanced from traffic.

- Enhanced infrastructure for sustainable mobility: Installing bicycle parking and infrastructure, green shelters, and pedestrian-friendly pathways to encourage eco-friendly commuting.

- Public awareness campaigns: Educating parents and local communities on the health impacts of idling vehicles and the importance of alternative transport options. Engagement of local health authorities and cities municipalities in educational events, publicity, and social dialogue.

The impact

The unique data from the “School Streets” project has already spurred significant changes in the pilot locations. Based on this research and in-depth interviews with the local community and local authorities, the initiative has prepared air quality improvement plans for five cities and new urban development concepts for school and kindergarten areas.

Some of the local governments have secured funding to implement changes in their plans, with others in the process of applying. School Street supported Nowy Dwór Mazowiecki to secure a PLN 225,000 grant from the Ministry of Education.

Another location also received funding to implement the proposed biking infrastructure solutions from the participatory budget (part of municipal budget, available for citizens’ proposals).

School Streets has demonstrated the feasibility of reducing emissions through strategic urban planning. During weekends and school vacations, NO2 concentrations decreased by approximately 10-30%, correlating with reduced vehicle traffic. This finding underscores the potential for even modest reductions in traffic to significantly improve air quality. The project is now scaling even further, by securing funding for three additional locations in Poland from InterCars Foundation, with implementation already underway.

By quantifying the link between traffic intensity and pollutant concentrations, the project provided irrefutable evidence of the urgent need for action. Community engagement efforts revealed strong public support for the proposed measures: 83% of parents consider air pollution to be a serious problem requiring immediate action, and 87% recognise the need to protect children from inhaling car exhaust fumes (according to a survey by Ipsos Mori for School Street Project).

By addressing both the root causes and immediate impacts of traffic related air pollution, the “School Street” initiative represents a scalable model for protecting children’s health while fostering sustainable urban mobility. The lessons learned in Masovian Voivodeship can guide similar efforts in other regions to provide cleaner air for future generations.