Air pollution is the fifth biggest killer by health risk factor worldwide. But this pressing global health and environmental issue is overlooked by development funders, including governments, multilateral development banks and bilateral development agencies.

90% of annual deaths from outdoor air pollution – over 4 million – are in aid-eligible countries. Improving air quality is critical to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Agreement. Yet there is no clear, over-arching strategy from the donor community to tackle this global crisis

As part of the State of Global Air Quality Funding 2022, we provide the only global analysis of international development funding for air quality in 2015-2021. We highlight the trends, gaps and opportunities for governments, multilateral development banks and bilateral development agencies. We also provide opportunities and recommendations for development funders to make smarter investments for people and planet.

Trends and gaps in in development funding

Only 0.5% of finance goes to air pollution

During 2015-2021, international development funders committed a $11 billion to projects tackling air pollution ($1.5 billion per year). This accounts for only 0.5% of total commitments by international development funders. For every $1,000 spent by a development funder, only $5 was spent to tackle ambient air pollution – the fifth biggest killer by health risk factor worldwide.

Air quality funding commitments are not enough to combat the scale of the problem and are declining. In 2020, international development funders cut their commitments to air quality projects in half and the trend is continuing in 2021, based on preliminary data.

More funding for fossil fuels than air quality

Between 2015 and 2021, international development funders committed $46.6 billion to projects that prolonged the use of fossil fuels. These projects received over four times more development funding than clean air projects.

A Global Burden of Disease study found that burning fossil fuels (coal, oil and natural gas) contributed to an estimated one million deaths globally in 2017, or 27.3% of all mortality. 80% of these deaths were in low- and middle-oncome countries. Fossil fuel-prolonging funding was distributed to South Asia (31%), the Middle East and North Africa (22%) and Central Asia & Eastern Europe (20%).

Most funding for fossil fuel-prolonging was channelled towards oil and gas extraction/production (64%), followed by natural gas (16%). International development funders must strike a balance between spurring economic growth in countries with large energy access gaps and minimising the financial and societal costs of locking-in harmful fossil-fuel infrastructure.

However, international development funders have started moving away from coal, with coal funding declining 95% between 2019 and 2020.

Loans are saddling countries with debt

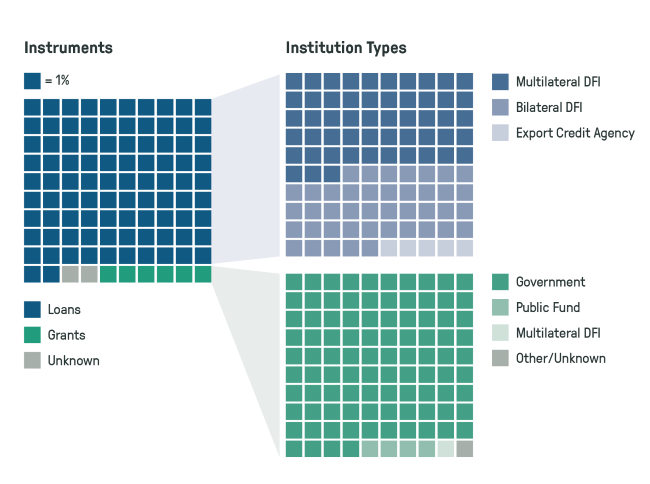

Grant funding, which is much needed to avoid saddling low-income countries with more loan debt, represented only 6% of total air quality commitments.

Multilateral development financial institutions (DFIs) provided 49% of air quality funding in 2015-2021, followed by bilateral DFIs (39%). These funders provided funding almost exclusively in the form of loans, which represented 92% of total commitments. Grant funding was mainly provided by governments. Loans can aggravate the growing debt burden in low- and middle-income countries who experience the brunt of climate change and need grant support to make a just transition to clean energy.

Only a few funders are tackling air pollution

There is still only a limited pool of funders providing air quality funding, leaving room for new investors to enter this space. Funding is often committed on an ad hoc and uncoordinated basis. Reporting on development funding with air quality benefits remains both limited and unevenly distributed.

Below are the top 10 international development funders, who represent 98% of air quality funding in 2019-2020. Among these, only four provided funding in the form of grants.

| Ranking | Funder | Air quality funding (USD millions) | % of air quality funding that is grants | % of air quality funding also targeting climate |

| 1 | Japan | 1,008 | 0% | 100% |

| 2 | Asian Development Bank | 669 | 0% | 53% |

| 3 | Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank | 250 | 0% | 0% |

| 4 | Republic of Korea | 201 | 1% | 95% |

| 5 | World Bank – International Bank for Reconstruction and Development | 100 | 0% | 0% |

| 6 | Germany | 57 | 100% | 7% |

| 7 | Clean Technology Fund | 16 | 0% | 0% |

| 8 | European Bank for Reconstruction and Development | 14 | 0% | 41% |

| 9 | United States | 14 | 100% | 11% |

| 10 | European Commission | 11 | 100% | 97% |

| = | All top 10 funders | 2,340 | 4% | 67% |

Case study: How China turned the tide on air pollution with ADB finance

As a result of rapid industrialisation and urbanisation, China became one of the most polluted countries in the world. In 2013, a study found that Beijing’s PM2.5 concentration was seven times the amount considered safe by the WHO. The dire state of air quality led the government to declare a “war against pollution”, stressing that the country could not allow itself to “pollute now and clean up later”. As part of concrete policy initiatives, China tasked the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei (BTH) region, one of the most polluted regions, and home to much of the country’s coal and steel industries, with a target to reduce annual PM2.5 by 25% by 2017.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB)’s multi-year project (2015–2023) helped deliver on the regional policy target. An initial $300 million loan targeted policy and regulatory reform in Hebei province; a second $500 million loan aimed at facilitating access to finance for small-and-medium-sized enterprises; and the third, most recent $500 million loan provided for an emissions-reduction and pollution-control facility.

- Refining policy infrastructure. Given the nature of air pollution, transboundary policies must be designed that consider geographical centres and peripheries as one integrated landscape. At the outset of the “war against pollution” China’s regulatory environment was instead fostering a patchwork of separate, locally based pollution control regimes. The Air Quality Improvement project established the necessary institutional arrangements and cooperation strategies for effectively managing a transboundary problem.

- Demonstrating and deploying new technologies. The pollution-control facility was designed to demonstrate the feasibility of technologies for heavy-emissions industries and enterprises. An industry-specific fund was provided for sub-projects within the iron and steel industries, as well as capacity building to use these advanced technologies and select appropriate business models.

- Catalysing finance. ADB’s investment is expected to attract approximately $1.5 billion in co-financing from other public and private actors, with the aim of training at least 200 people in the use of advanced technologies by 2023. Development finance institutions can play a key role in establishing the market for, and de-risking, pollution-reducing technologies and enterprises.

- Improving public health. Progress has already been observed in the BTH region: since 2013 there has been a 49% reduction in particulate pollution, translating to a gain of 4.1 years in life expectancy.

International public climate finance is a missed opportunity

Just 2% of international public climate finance – the share of international development funding contributing to the goals of the Paris agreement – explicitly tackles air pollution, despite these problems sharing the same root causes.

$7.6 billion of air quality funding (72%) simultaneously addressed climate change, largely via mitigation projects in the transport and energy sectors.

Our climate, air pollution and health challenges are interconnected in their causes and consequences, and therefore also in their solutions. Despite this, action is often handled separately, with siloed air quality and climate policies potentially leading to both damaging trade-offs and missed opportunities.

If funders account for the health and economic benefits gained from improved air quality in their programming, their investment becomes better value for money with increased impact. If impacts on air quality are not considered at the design phase, climate projects that might actually be net-benefit might still appear as net-cost, and potentially not go ahead. It can also lead to more climate action because air quality benefits can be quick wins and build public support for further steps.

Chile: Joining-up action on air quality and climate

Chile is particularly vulnerable to climate change and is already experiencing its impacts, most notably through an ongoing drought since 2010 in the central and southern part of the country. Chile is also home to 11 of the top 15 most polluted cities in Latin America and the Caribbean with air pollution costing the Chilean health sector approximately $670 million every year, associated with 4,000 premature deaths. Despite this, Chile did not receive any air quality funding from international development funders during 2015-2021.

In April 2020, Chile submitted their revised Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the UNFCCC, outlining their strategies for tackling climate change. One component of the NDC committed the country to reducing black carbon emissions by 25% by 2030, relative to 2016 levels. Black carbon is a component of PM2.5 that directly contributes to atmospheric warming as well as being a dangerous air pollutant. Hence, Chile’s decision to integrate black carbon reduction targets into its NDC is an important step towards joined-up action on air quality and climate, linking international climate policy processes with local air quality concerns.

As black carbon in Chile mainly comes from burning firewood for heating and residential cooking, biomass-based power generation, off-road machinery and diesel vehicles, actions proposed to deliver on this target include switching to electric heating, energy efficiency improvements, industry emissions standards, as well as more stringent transport regulations.

Alongside other countries that have adopted similar black carbon targets within their NDCs, Chile has set an example of how joined-up action may be operationalized, using and enhancing the existing policy infrastructure established for tackling climate change to achieve broader social and economic gains. Moreover, integrating immediate, local air pollution concerns – that have tangible implications for individuals – into longer-term climate strategies helps to increase buy-in on NDCs, allowing benefits to be realized today rather than sometime in a distant future.

Capitalising on the shorter time frame for delivering air quality outcomes and, thereby, delivering on longer-term climate goals that span multiple political cycles, is a key opportunity joined-up action offers to policy makers.

Africa, Latin America and most of Asia are missing out

Air quality funding was concentrated in a handful of Asian countries, while regions such as Africa and Latin America lagged behind.

Recommendations

Building on our overall recommendations for all funders, below are further actions for international development funders:

1. Develop and coordinate a global donor strategy – spearheaded by champion governments – that aims to increase spending effectiveness, and leverage from international public finance in reducing global air pollution. This means:

- A marked uplift in the scale of air quality spending worldwide, including efficiencies made by having a more joined-up approach with climate action and integration into infrastructure and service investments.

- Systematically capturing and communicating the health, environmental and development benefits of air quality expenditure to build awareness of it as a unique investment and impact opportunity.

- Actively seek a wider geographic spread in clean air investment portfolios.

- Using innovative financial instruments such as outcome based finance, guarantees and de-risking for eligible projects, to catalyse further investment in the clean air space.

- Committing to improve reporting of development funding of air quality to help better coordinate development activities, especially where funding comes from multiple government departments or agencies.

2. Increase the volume of grant-based funding to tackle the inequitable air pollution-related disease burden in low- and middle-income countries. The majority of air quality funding is provided in the form of loans, which may aggravate the growing debt burden in low- and middle-income countries. Increasing the grant component of air pollution development assistance can help kickstart pollution-reducing projects in countries with limited public resources, and help to address the disproportionate air pollution-related disease burden they face.

3. Phase-out all new investments in fossil fuel-prolonging activities while significantly upscaling investments in new clean technology and energy. Despite increased political momentum to phase out fossil fuels, development funding to fossil fuel-prolonging projects still outpaces air quality funding fourfold, jeopardising the clean air agenda, global climate goals, and development objectives more generally. Fossil fuel funding should be in exceptional cases only and should diminish swiftly, with the priority placed on investing in a just, clean transition.